The King, Edson Arantes do Nascimento, known as “Pele”, died on December 29, 2022. He was the undivided champion of the game, the only player to have won three World Cups, in 1958, 1962 and 1970.

The Brazilian, simply Pele, was a king of soccer without competition. Other players like Jairzhino, Cruyff, Platini, Maradona, Zidane, Ronaldhino, Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo. His legendary feat of arms, these 1,283 goals scored in 1,366 games and twenty years of career, a record inegal, since the 1970s, modern soccer and its scientific methods.

Pele, is the only player to have won three World Cups, in 1958, 1962 and 1970

As a youngster, Pele was skinny but with a Marvel-like technique, he was a comic book hero. He was gifted with both feet and head, barely over 1.70 meters tall, but with an incredible vertical leap and a great reading of the game.

Pele was an artist and stadiums, like the Maracana in Rio de Janeiro, were an arena where the best player of all time played with the defenders.

His greatest achievement and best World Cup was in Mexico in 1970, in the final against Italy. He did everything to the Italians, completely overwhelmed by the talent of Pele, the Italians practicing the “catenaccio” and the Brazilians with Pele in the lead, a soccer “Champagne” festive to wish. Pele left the competition in triumph, shirtless, lifted like a trophy by the crowd at Mexico City’s Azteca Stadium.

In 1970, for the first time, the homes equipped with TV, had been able to admire the idol in color, in his light suit, auriverde, gold and green. Pele had propelled Brazil to a third title with a header, after rising above Milan defender Tarcisio Burnish, who was several centimeters above him and had to extend his arm in desperation. I told myself before the game that he was in the flesh, like all of us,” lamented his bodyguard. I realized later that I was wrong.

Pele had retired from international football, and on July 18, 1971, in a friendly match at the Maracana against Yugoslavia, Pele appeared for the last time in a Seleçao shirt. Without him, it would not be the same. In fifteen years, he had made soccer a party.

Pele was born further north-east, on October 23, 1940, in Tres Coraçoes, a small town in Minas Gerais, whose inhabitants’ lives had been transformed by electrification. That is why he was given the name Edson, in homage to Thomas Edison.

At the beginning, the sluggish student, who worked in small jobs, such as a shoeshine boy, had discovered his dexterity by juggling knotted socks or grapefruits. He writes: “My father saw that I was small and rather skinny (…). Since I couldn’t push others out of the way or jump higher than them, I just had to be better at it. I had to learn to make the ball an extension of myself.”

Soon, he was spotted by Waldemar de Brito, a former international who took part in the 1934 World Cup. This mentor accompanied him to present him as the future “greatest player in the world” to the Santos FC management. Pele described the club as “modest” before his arrival, which was not true. The “Fish” from the port city of Paulo, dressed in white, were the two-time winners of the Sao Paulo regional championship, the most prestigious one along with Rio. The immensity of the country, the problems of transport and the lack of financial means did not allow the creation of a national league before 1971.

In June 1956, the young Pele signed his first professional contract. He was only 15 years old, and De Brito’s prophecy was soon fulfilled. On his debut with the Santos first team, he immediately scored the first of many goals. Ten months later, in July 1957, he was called up to the national team to face the Argentine enemy at the Maracaña.

When Pele took the field in Gothenburg for the Auriverde’s third group match against the Soviet Union, he became the youngest participant in the history of the World Cup at 17 years old. Then his youngest goal scorer, when he delivers his team in the quarterfinals by breaking the Welsh resistance (1-0). Finally, his youngest finalist and winner by settling for a double against the Swedes (5-2). In the semi-finals, the French of Kopa and Fontaine had been inflicted the same punishment to the score by the fault of a triple of the striker.

Finally, Brazil had won the Jules Rimet trophy and forget the drama of the “Maracanaço” of 1950, the unexpected defeat, at home, in the final against Uruguay. This victory was based on the complementarity between its two wonders, the other being the crazy dribbler Garrincha, the “angel with bent legs”, in the words of the poet Vinicius de Moraes, the people’s boy and the Botafogo bird. “Mané”, the tragic double of Pele the solar. When these two were lined up together, the Seleçao never lost a match.

Thanks to Pele, Santos officially became the best team in the world, thanks to its victory in the 1962 Intercontinental Cup, against the other Portuguese-speaking giant, Eusebio’s Benfica. In Lisbon, they won 5-2, with Pele scoring a hat-trick in weightlessness. The Paulist club will keep its South American and planetary supremacy during the following editions, by folding the Porteños of Boca Juniors, then the AC Milan.

The whole world wanted to see Pele and the stadiums of the Americas, Europe and Africa demanded Pele and the “Santasticos“, embarked on an exhausting cycle of tours and gala matches, on the model of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball players. In 1960 and 1961, they participated in the Paris Tournament, which they won at the expense of Racing and Stade de Reims. Offers from the biggest European clubs – Real Madrid or AC Milan – were pouring in to attract the nugget. But as he would do to protect a work of heritage, the short-lived president Jânio Quadros decreed Pele a “non-exportable national treasure”.

After the failed 1966 World Cup, he was disgusted and imprudent, Pele announced in the wake of the World Cup that he would no longer play in the World Cup, as it did not protect the creators enough and did not sanction the increasingly physical game of the Europeans. We know what happened next: his brilliant revenge four years later in Mexico, an edition marked by the introduction of cards.

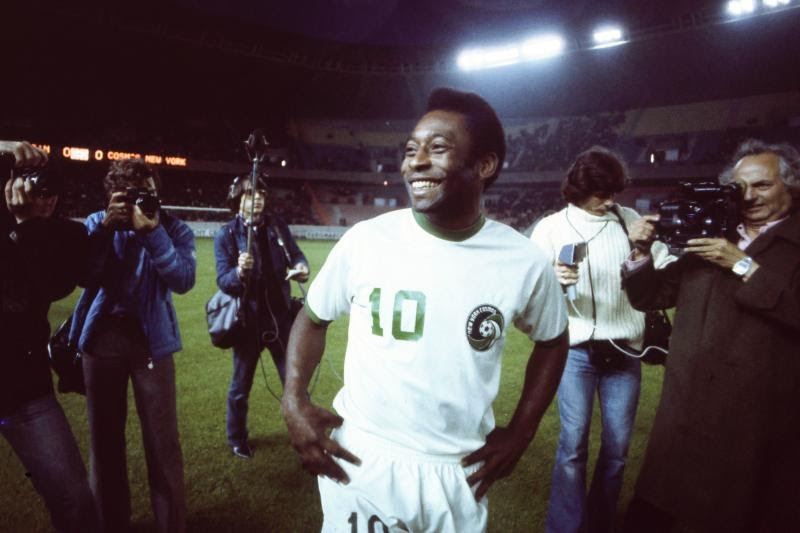

Pele refused all offers from England, Italy or Spain and after nineteen seasons with Santos, the “Rei” came out of semi-retirement to become the “King of New York”. At 34 years old, he gave in to the sirens of the new North American League and especially to a golden bridge, with an annual salary of 1.4 million dollars over seven years, a record at the time.

In 1974, he finally accepted the proposal of Warner, owner of the Cosmos club, especially because this naive man was riddled with debts, dug by an indelicate entourage. It will take the intervention of one of his admirers, the American Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, to overcome the resistance of the military junta in power in Brasilia and to allow him to leave.

He was the first to sign with an American club in order to develop soccer in the United States, later joined by other glories, such as the Italian Giorgio Chinaglia, the “Kaiser” Franz Beckenbauer or his compatriot Carlos Alberto. In August 1977, he won his last trophy, the North American championship, and two months later, in front of 70,000 spectators at Giants Stadium, he retired for good in a farewell match between the Cosmos and Santos. He played one half in each of the only two teams he knew, and scored his last goal with a free kick.

Pele was recruited by the UN and UNICEF, but he did not give up the limelight. In New York, he tasted the delights of the jet-set by becoming an attraction of the famous Studio 54, introduced in the local fauna by a former footballer, the Scottish rocker Rod Stewart.

King Pele touched politics, accepting, in 1995, the sports ministry proposed by the new president Fernando Henrique Cardoso (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, center-right). The first black man in his country to head a ministry, he remained there for three years, managing to get a law passed in his name before he left which, according to him, “freed all Brazilian footballers from slavery”.

Pele was courageous and went to war against corruption and the two satraps of Brazilian soccer, Ricardo Teixeira, president of the federation, and his father-in-law, Joao Havelange, Sepp Blatter’s predecessor at the head of FIFA. Powerful lobbies were active in trying to gut the law.

“People ask me all the time, ‘When will a new Pele be born?’ Never! My father and mother closed the factory,” he had declared in these columns, to cut short any question of inheritance, before adding, “Pele is the greatest name known in the world.”

With him, the aplomb and the boastfulness were permanently mixed with joy. Everything was excess, and excess was contagious. “Pele is one of the few people to contradict my theory: instead of fifteen minutes of fame, he will have fifteen centuries,” said Andy Warhol, who was to immortalize the icon in 1977 in his New York studio. With a portrait of Pele as he was: smiling, highlighted with optimistic blue and green, the ball stuck to his forehead, ready to take a header.

Comment here