By MDS – C19 Staff , December 8 2020

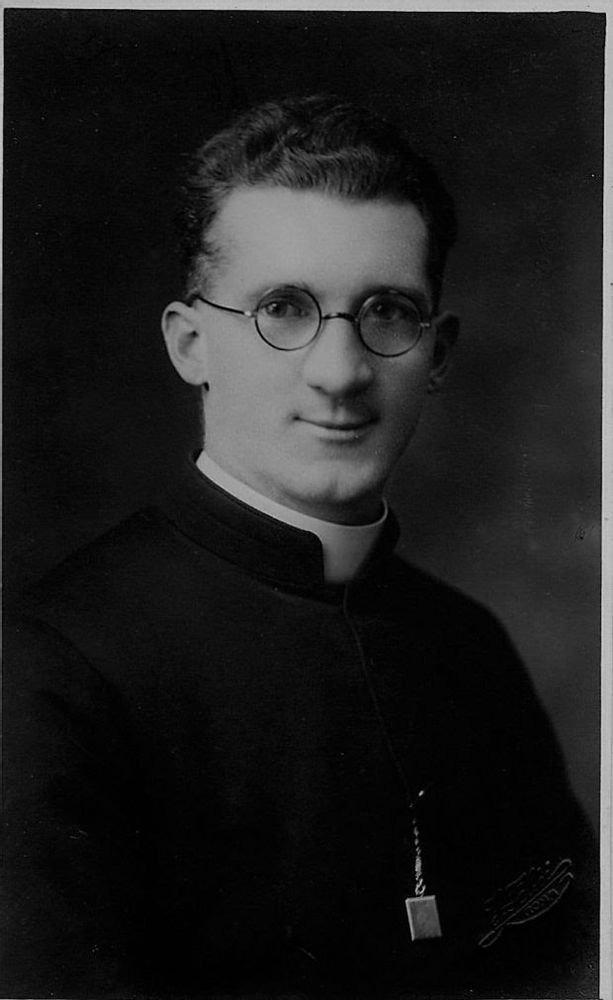

Monsignor O’Flaherty

Monsignor O’Flaherty, the son of a steward at the Killarney golf course, was fluent in Italian and German, held three doctorates and was an amateur golf champion. But his real claim to fame was as the “Vatican Pimpernel” in Nazi-occupied Rome in the second World War. As the lead behind the “Rome Escape Line”, he saved the lives of six and a half thousand prisoners of war, partisans and Jews. And he did it all with considerable panache from his HQ in all places the German College, nestled right beside Saint Peter’s Basilica.

Despite a 1980s TV film starring Gregory Peck and honours showered on him by the Allied nations, Italy and Israel after the war, he is hardly a household name. Yet, he has been called the Irish Schindler who took on the Third Reich in a daring operation, sheltering fugitives in convents, monasteries and Italian homes.

He smuggled out Jewish people disguised as nuns and monks, passed partisans off as Swiss guards and hid the thousands of prisoners of war who flocked to him on the steps of St Peter’s. They were seeking the sanctuary of the church at a time when Hitler recognised the Vatican’s neutrality, all under the noses of Nazi guards. He was also fond of the odd disguise himself – once as a coalman to evade a Nazi raid on a palazzo. He was even rumoured to have dressed as a nun.

He was a strikingly modern figure in so many ways: ecumenical, well connected, compassionate to all-comers. Like his fellow Kerryman Tom Crean, he engaged with the British in an enterprise that transcended national borders. His story is one of humanity against oppression, where “God has no country” in his striking phrase.

From "deicide people" to "elder brothers in the faith".

While pagan anti-Semitism can be found long before the appearance of Christianity, Christian anti-Judaism flourished for centuries until the turn of the Second Vatican Council.

How was Christianity, based on the teaching, the person and the life of a Jew, the son of a Jew, whose first disciples were Jews, responsible for centuries for what the historian Jules Isaac called "the teaching of contempt" towards the Jews?

In medieval times, the myth, already existing in antiquity, of ritual murders committed by the Jews spread. It is noteworthy that the Holy See most of the time stayed away from these rumors. Thus, while many accusations of ritual murders attributed to Jews came from Germanic countries, Pope Innocent IV rebelled against these "evil machinations" with a bull sent to the German bishops. Ho . wever, some children whose murders were attributed to Jews were publicly venerated, such as little Simon of Trent, who disappeared in 1475. This affair, which led to 15 executions in the small Jewish community of the city, was recognized as fraudulent in 1965 by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

Modern anti-Semitism, however, is clearly distinct from the "teaching of contempt" held by the Church for centuries: hatred is no longer religious in nature, but racial. But, according to Jacqueline Cuche, "the centuries of religious anti-Judaism that preceded the antisemitism born in the nineteenth century allowed it to wreak havoc. In the midst of the Dreyfus affair, La Croix proudly proclaims itself "the most anti-Jewish newspaper in France"…

Since then, the popes have all recalled that anti-Semitism is a sin and that being both Christian and anti-Semitic is incompatible. Before the Jewish community in Germany on November 17, 1980, John Paul II spoke of the "people of God of the Old Covenant, which has never been revoked. "You are our favorite brothers and, in a certain way, one could say our elder brothers," the same pope said in 1986 in a speech in the synagogue of Rome.

In the USA, Hanukkah and Christmas are celebrated together and this has strengthened Judeo-Christian relations.

It happens every year. Interfaith families face the “the December dilemma” over how they will handle Christmas and Hanukkah, which generally fall within the same month. It has become a common issue in a world in which 50 percent of American Jews are married to people who are not Jewish, and who are, most often, Christian, or of Christian heritage. This year, Hanukkah begins on Christmas Eve, making the negotiation of these holidays potentially more complex. Many interfaith couples and families will try to decide how to include or exclude two traditions worth of memories, stories, theologies, rituals, and recipes. Like the holidays themselves, the solutions that couples have found have continued to evolve over time.

For the contemporary interfaith family, the options for negotiating the “December dilemma” have proliferated. The dilemma is no longer a matter of trying to sort the acceptable from the unacceptable options. Rather, it’s a choice among the many practices available. This year, Hanukkah and Christmas may be together again, but their distinct celebrations can be as varied as the many families who observe them.

This year will be special because Israelis and Christians will be praying for an end to this terrible pandemic and the Covid 19.

Happy Hanukkah, Merry Christmas

Clémence Houdaille

Samira Mehta

Comment here