South Asia, a region with a combined population of nearly two billion people, is facing its worst health crisis in recent memory. India and its neighbours are seeing a ferocious spike in coronavirus infections, leaving smaller countries like Sri Lanka particularly vulnerable.

However, China is ramping up its relief efforts in these countries, which experts say could strengthen its influence there.

On Friday, the streets of towns and cities across Sri Lanka will fall silent once again – people there will only be able to venture out of their homes for essentials until 25 May.

Like its neighbours, Sri Lanka largely coasted through a milder first wave last year, but has been seeing a recent surge in Covid cases which is threatening to overrun its healthcare system.

It is now reporting around 3,000 cases a day which is a more than 1,000% rise from a month ago.

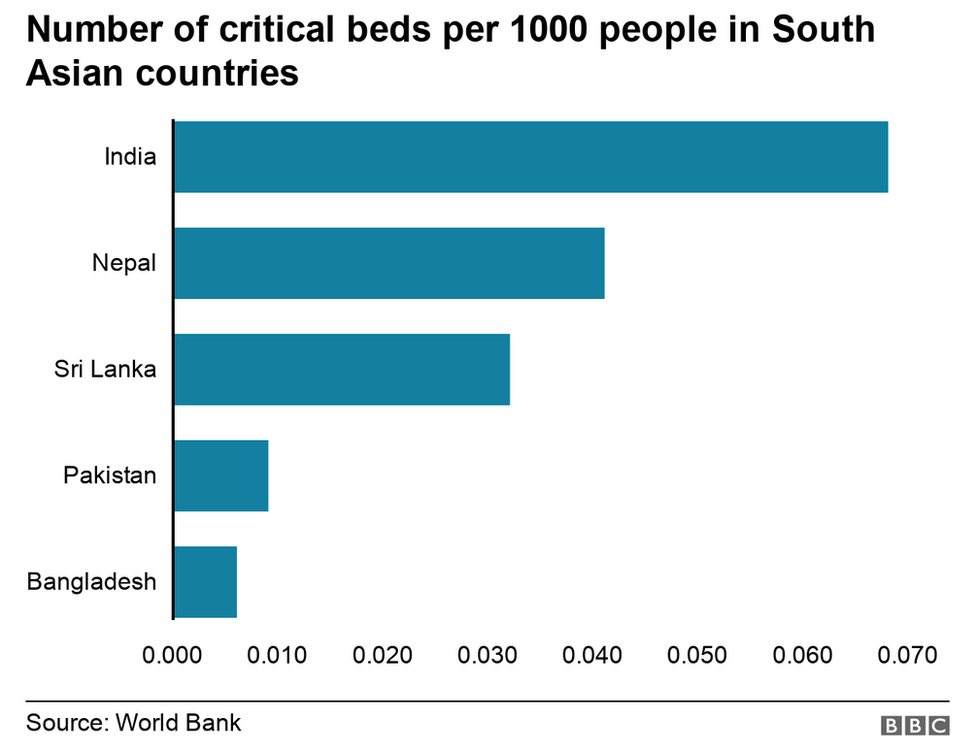

And despite having a largely free, widely accessible public health system that is regarded as the best in the region, hospitals in the island nation of 21 million people are struggling to cope.

“We have limited capacity to control a surge. We are good, the healthcare system is great as long as there is not a surge in the pandemic, as long as the system is not challenged as much,” public health expert Shashika Bandara told the BBC.

But Sri Lanka’s government is also being criticised for not doing enough to contain the spread.

There is not enough genomic sequencing of new cases, although the UK variant is widely believed to be responsible for the spread.

And experts like Dr Ravi Rannan-Eliya, the executive director of Sri Lanka’s Institute for Health Policy, say that there is “a high probability – greater than 50% – that the B.1.617.2 or Indian variant has also been in the community since at least April”.

Despite the surge in India, a “travel bubble” between the two countries was not halted until early May, causing much public anxiety.

And the government hesitated for weeks to impose restrictions on travel and movement, despite warnings from public health officials that Sri Lanka stood to face an “India-like situation” soon. Many people travelled freely in April as the country celebrated its traditional new year.

Efforts to vaccinate against the surge have also hit roadblocks.

Sri Lanka began vaccinating people earlier this year, and was largely dependent on India for supplies of the AstraZeneca vaccine. But with the situation worsening there and shipments stopping, the programme had to be halted.

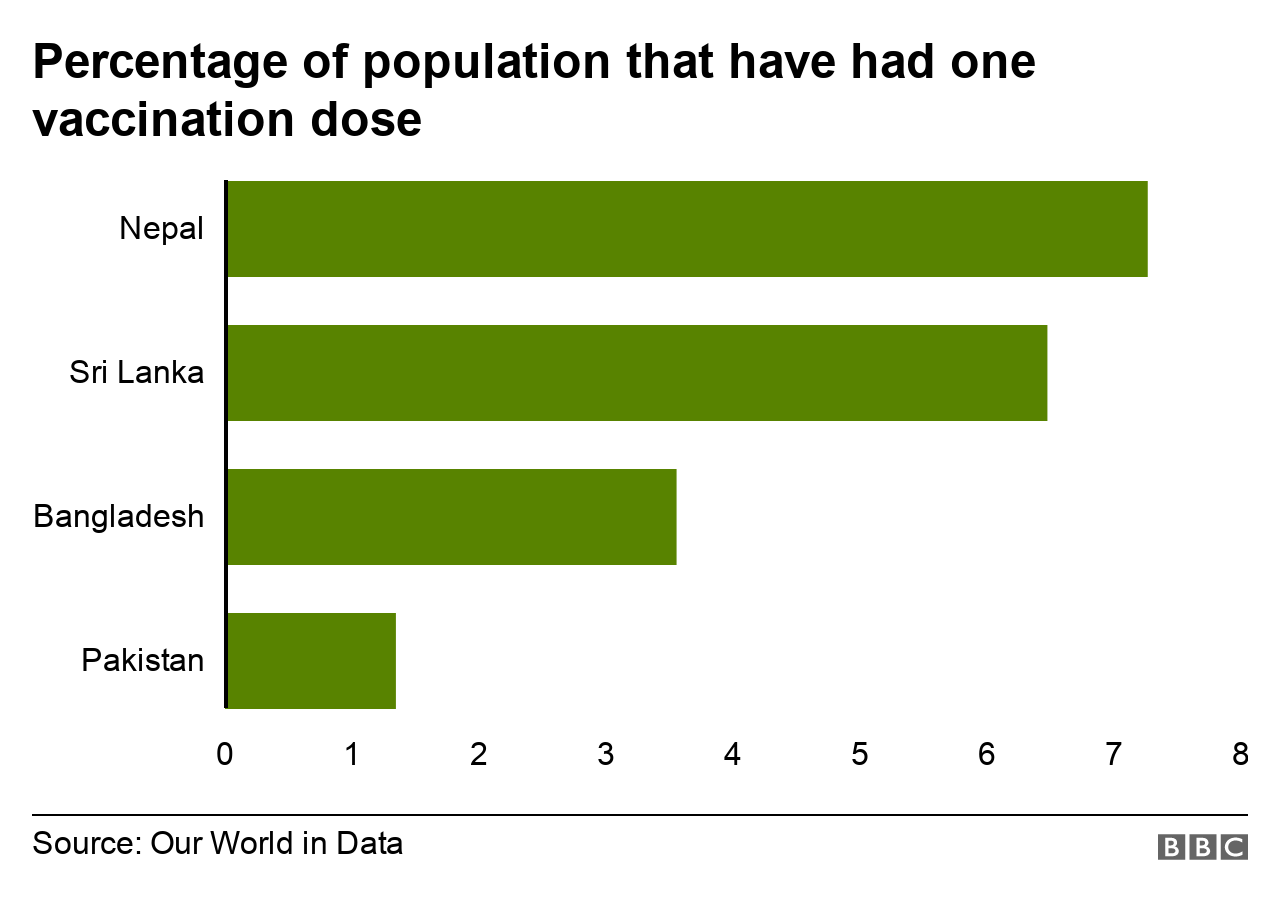

As of 19 May, just over 6% of the population had received one dose of a vaccine and there’s a great deal of uncertainty over how or when those who received the AstraZeneca jab will get their second dose.

Enter China.

The Asian giant – which already has a significant presence in many of India’s neighbours, including Sri Lanka – has been at the forefront of relief efforts here, donating vaccines, personal protective equipment (PPE), face masks and testing kits in efforts that are being called “face mask” diplomacy.

And along with Russia, it has also been able to make up for the shortfall of vaccines left after India’s inability to keep providing them.

China has donated 1.1 million Sinopharm vaccines to Sri Lanka which has helped resume its vaccination programme and the government has announced plans to purchase more, along with Sputnik.

Experts say Sri Lanka has been exemplary in deploying vaccines for infectious diseases in the past and so people are not as hesitant about the Covid-19 vaccine as elsewhere in Asia.

There was some concern over the Chinese and Russian vaccines, but as cases have surged, people have been queueing up to get them.

Beijing is also already providing financial assistance to Sri Lanka as its economy struggles under the strain of the pandemic.

But some policy experts worry that this will only strengthen what critics refer to as China’s “grip” on Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka, along with other countries in the region that China is helping with Covid crises – Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh – are integral to Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative, a sweeping infrastructure project that aims to expand global trade links.

In fact, Beijing has been investing billions of dollars in infrastructure and development in Sri Lanka for several years – leaving some locals to feel like the country is being sold to the Chinese.

A port that was built by Chinese companies and Chinese funds at Hambantota – which Sri Lanka has not been able to repay and therefore handed over to Beijing – has fuelled anger, as have plans to build a brand new city with Chinese money off the coast of Colombo on reclaimed land.

China’s so-called string of pearls strategy – an attempt to expand its influence in South Asia – is controversial, and has long been watched with particular suspicion by its regional rival, India. But with India struggling to contain the pandemic ravaging its population or help halt the spread of infection, there is very little Delhi can do.

“China’s vaccine diplomacy will add another layer to the existing Chinese infrastructure diplomacy in the island. The Chinese sphere of influence in the island will grow further with vaccine diplomacy,” political analyst Asanka Abeyagoonasekera told the BBC.

But Dr Rannan-Eliya says countries like Sri Lanka need China right now, because it is the only country manufacturing Covid supplies at the scale required and also because of its success in containing the pandemic.

“The big mistake is we didn’t take the Chinese playbook seriously,” he said, referring to Beijing’s multi-pronged approach of lockdowns, contact tracing, shutting borders and testing at scale.

“We copied the British playbook, but if you look at countries like New Zealand, they also copied China”.

Comment here